BY GUILLERMO HEVIA

Commonplace and

New Concepts

Latin America is at risk of

becoming a kind of “registered

trademark,” a prescriptive, ambiguous, diffused,

and exotic concept, from

which architecture and its diffusion has been profitable

and accepted almost without question, to the point of

becoming a certain truth.

![]()

![]()

The concept, if it does not expand towards new arguments and global debates, is at risk of becoming prescriptive and limiting, turning inwards towards itself and based on a set of arbitrary values associated with landscape, material, artisanal construction, precariousness, and the social, which is deeply rooted in a material reinterpretation of the modern movement or in an exacerbation of physical and material deficiencies under the label of communal or social. The precarious is considered a value instead of a problem that must be faced by architecture.

The phenomenon of “Chilean architecture” is an example of the construction of arbitrary and limiting editorial narratives, which during the last two decades has filled magazine covers and has been presented in biennials and exhibitions, from a perspective limited almost exclusively to unique constructions in the middle of remote landscapes or in some attempts to deal with social issues. This fact has left out the work of entire generations and a whole group of works that deal with the public and the urban dimensions. The Chilean phenomenon is a good example of an artificial, biased, and currently exhausted editorial concept, which later produces a generational, conceptual, and theoretical vacuum that is difficult to ignore.

Is there room in the concept of “Latin America” for topics such as typology, program, envelope, or ecology? Is “Latin America” developing a new theoretical or historical production that does not continually return to the modern movement or social aspects?

![]()

![]()

![]()

The above diagnosis is not absolute and is full of exceptions. Nor does it seek to establish a negative judgment, but rather seeks to generate an alert about the need to broaden the spectrum of topics, discussions, and perspectives, not limiting exclusively on past and current certainties, but rather opening up to contemporary uncertainties and speculations, transforming exceptions into rules and diversifying the matrix of concepts and projects, allowing a new conceptual coexistence.

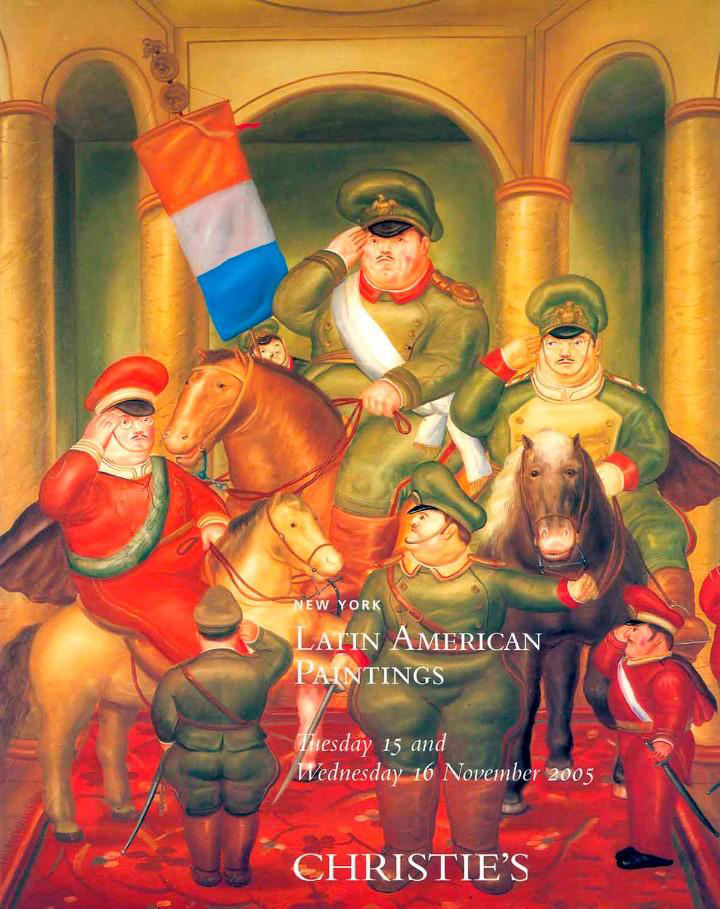

This idea is followed by a provocation that seeks to question the concept, the commonplace, and the cliché that “Latin America” can represent in the world, and end with the lucrative label of the exotic, which has a simile in how the art of the region is presented in auction houses in “first-world cities” like New York, and their concept of “Latin American art.”

This phenomenon of conceptual simplification and reduction must be overcome to allow a broader and more diverse discussion, in which new actors must be incorporated. Would the productions of Amancio Williams, Clorindo Testa, Emilio Ambasz, Cesar Pelli, Adamo Faiden, Rafael Viñoly, Enrique Norten, Alberto Kalach, Borja Huidobro, Smiljan Radic, Elemental or Giancarlo Mazzantti enter into this “Latin American” canon? Probably not. Are they, therefore, less “Latin American”? Should there even be the label “Latin American”?

![]()

![]()

Probably one of the values of the production of these architects lies in a deliberate abandonment of the modern and mono-material tradition that has dominated the architecture of the region, to open up to explore new concepts and experiment with materials other than exposed reinforced concrete. It is not by chance that these architects have managed to create studios with a more complex degree of organization, which has allowed them to access projects of greater scale and complexity, and that many of them are even based and working outside their countries of origin.

This condition explains the fact that for an architect in Latin America it is almost impossible to sustain a career in an office over time, which has an impact on the existence of a large number of young offices, with little experience, that have quality built work and in quantity, but limited to the small scale, and which for the same reason, transform the building and the construction into their main argument. This ability to build at an early age is undoubtedly a strength of the region, but at the same time, it is its main problem and limitation.

A common condition in the region is a university system that confers professional degrees that enable architects to build once the undergraduate degree is completed, without the need for previous experience or higher requirements. To the above, we have to add a precarious professional structure, unprofessional and poorly paid, which tends towards independence rather than professionalization.

The impossibility of generating an organized professional structure forces architects to focus almost exclusively on small-scale individual production, which creates a vicious circle that prevents them from acquiring more experience and turning the office structure into something more complex that allows them to get involved in larger-scale projects. Architects end up being prisoners of the same assignments — usually single-family houses or small interventions — and of their ideas of purity and material radicality, which are not always compatible with more complex projects, where the actors and forces involved increase, and therefore negotiation upon the building becomes a fundamental variable.

The "material architect" does not usually negotiate, he becomes a prisoner of his comfort zone and his prejudices.

At the same time, it is in the midst of a cultural environment that celebrates and exacerbates these values, while projects of public relevance end up in the hands of a handful of offices, generally with low-quality production, but with sufficient bureaucratic organization and experience to access these projects, and above all with the ability to yield and negotiate in a dynamic of forces that exceeds the artisanal scale.

Today’s global challenges are related to climatic and ecological topics. Architecture is an instrument that must be capable of addressing and transforming these challenges. Latin America should be a key player in these discussions, as it has a unique climatic variety, the greatest biodiversity

in the world, the largest freshwater reserve (excluding Antarctica), the countries with the highest percentage of the indigenous population, and some of the most populated cities around the world.

Ecology, Nature, Climate, Energy, Infrastructures, City, Housing or Public Space are arenas towards which the architectural production in Latin America should diversify and with generations that are capable of shifting scale, negotiating and diversifying their conceptual platforms, thus overcoming the certainties and prejudices of the past to face a new future.

Neither regional nor global, an architecture without a designation of origin.