by Alice Fang

“The Brazilian machine of living, during the colony and the empire, depended on this mixture of things, animals, and people, who were the slaves. If the old time’s remaining mansions seem uninhabitable due to the discomfort, it is because the black is absent.”1 In Brazil, the paternalistic

discourse at the center of domestic relations prevails. An empregada is treated “practically as if she were someone from the family.” However, she is never entirely accepted, as the word “practically” suggests. This play of social relations in the domestic sphere between “maids” and employers

generates a performative act of asymmetrical power entrenched in class, race, and gender issues. The ubiquity of domestic labor in mid-and high-income households renders the invisibility of the employment of “maids” in Brazil. In investigating domestic households’ spatial genealogy, the quartinho de empregrada emerges as the stage where

the power performance occurs. The existence of this room today is the result of historical and cultural changes that shaped service spaces as far back as the sixteenth century. By tracing and quantifying a variety of domestic worker spaces in São Paulo’s residential buildings, this essay

aims to foreground how the quartinho manifests as a neglect of domestic workers’ quality of life in Brazilian households.

Scene from Que Horas Ela Volta? (The Second

Mother), movie directed by Anna Muylaert.

Lexicon

In the essay, the employment of Brasileirismos (“Brazilianism”) — words

or phrases specific to the Brazilian lexicon — provides nuance and specificity to initiate the conversation around domestic labor in Brazil.

Portuguese is a gendered language. The words empregado (masc.) and

empregada (fem.) translate into “employee.” However, when referring to

empregada, the term used directly refers to a “woman employed for domestic services, maid, housekeeper.” The counterpart of the empregada

is the patrão (masc.) and patroa (fem.) — “employer, boss.” In this case,

the use of both terms is frequent, although patroa has a predominant

presence in this interplay as “the mediator between her family’s needs,

standards, and desires and the maid’s ability to deliver the service.”2

The term quartinho de empregada is most commonly utilized in referring to the housekeeper’s room within a Brazilian household. The expression signifies “little maid’s room.” It is not only suitable to depict the physicality of the room, which is often small, dark, hidden, and poorly ventilated, but also carries a pejorative meaning that undermines the value of domestic labor.

Complexity

According to the International Labor Organization, the number of people in the Brazilian domestic labor sector exceeds the population of Denmark.3 However, the scarcity of research around this theme is not nearly proportional to the ubiquity of domestic labor. The notion that todo mundo tem empregada (“Everyone has a maid”) is so entrenched in this context that it has thoroughly permeated the daily lives of middle- and upper-class families. The universality of employing empregadas to execute daily chores of cleaning, cooking, and babysitting renders an unspoken power relation between the “maid” and the families for whom they work.4 The employer must find just the right balance between being a nice patrão/patroa and remaining a figure of authority. Even among academics, leftists, and feminists, there is little interrogation of the widespread phenomenon of paid domestic service and the home as a place where inequalities are perpetuated.5 The acknowledgment of the authoritarian dynamic between patrões and empregadas is critical to start unveiling the layers of complexity that are deeply rooted in class, race, and gender.

Quartinho de Empregada

It could be argued that the history of slavery in Brazilian society, which governed domestic workers in rural and urban houses during the Colonial Period, can be tied to the late construction of labor rights for domestic workers in the 20th century.6 Regulation of the profession began only in 1972, with Lei Presidencial n.º 5.859, a law that acknowledged and granted rights to domestic workers. In 1988, with the new Federal Constitution, other rights emerged, such as weekly paid rest.7

A study from the Institute for Applied Economic Research (Ipea) indicates that approximately 7 million Brazilians are registered in domestic labor positions, or three domestic workers for every one hundred inhabitants.8 Remarkably, 92% are women, mostly black with low education, and from low-income families.9 With no prospect of better living conditions in their hometown, the “maid” often migrates from the countryside

to the metropolis. As a heritage of the Colonial slave quarters, the culture

of hiring “live-in maids” was prevalent before the regulation of domestic labor.10 Thus, there was a need to maintain the service room, or quartinho de empregada, in the dwellings’ functional composition. Because

the “maid” wakes up at the employer’s home, working hours are never

really defined — morning, afternoon, night, or dawn, if necessary.11 The

primary issue with the quartinho revolves around this culture. Even if the

empregada had not come from the countryside, even if she had a permanent home and a family in the same city where she works, it was culturally “agreed” that she slept at the employer’s house during the week.12

This way, she could work from very early to very late, without excuses to miss work.13 She could return to her home during the weekends when

allowed.14 This situation produces difficulties measuring extra working

hours since the delineation of days and nights is unclear. In other words,

overtime is inherently expected. Additionally, the empregada has little privacy, as the quartinhos are usually located near busy and noisy kitchens

and laundries.15 These rooms are usually extremely uncomfortable, given the small size and lack of natural ventilation and lighting.16

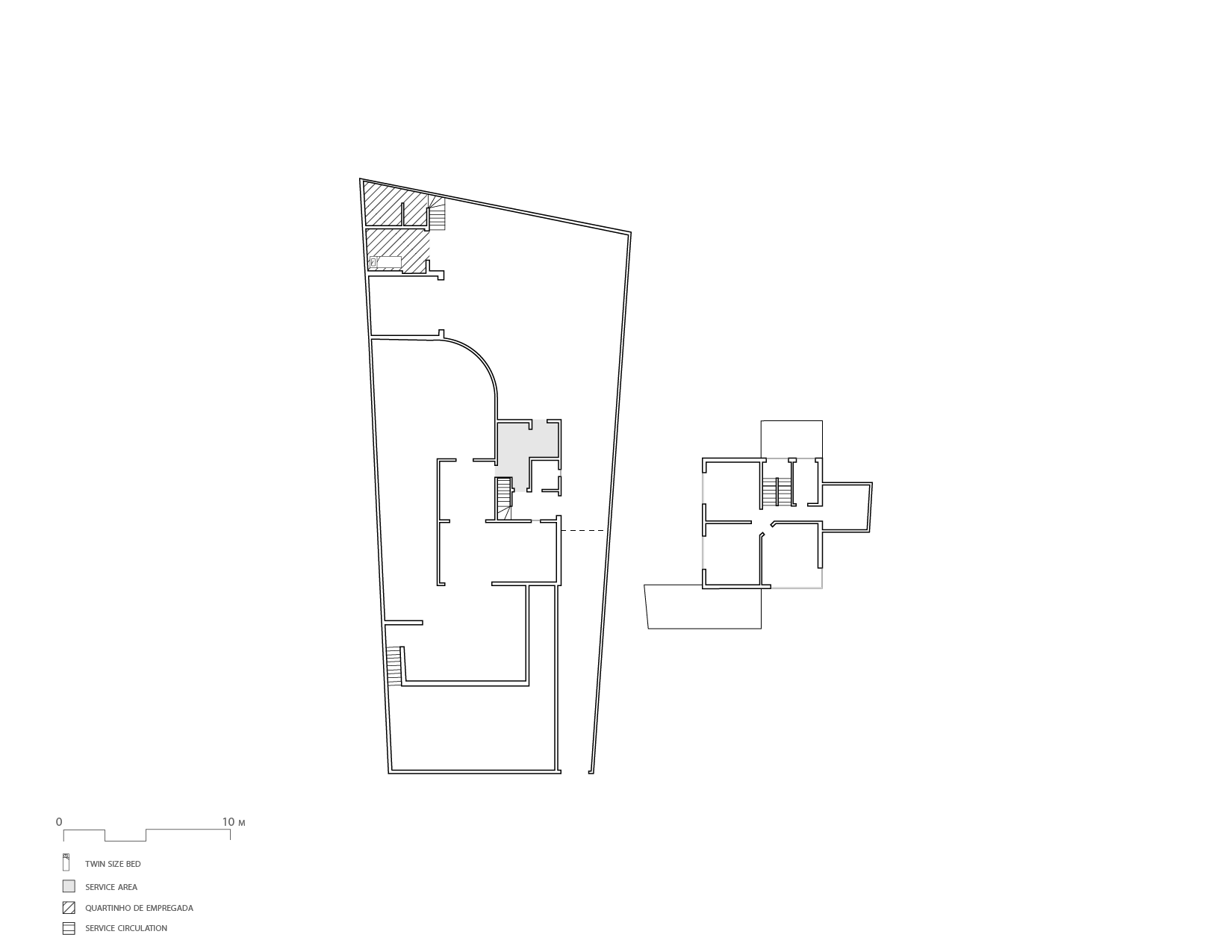

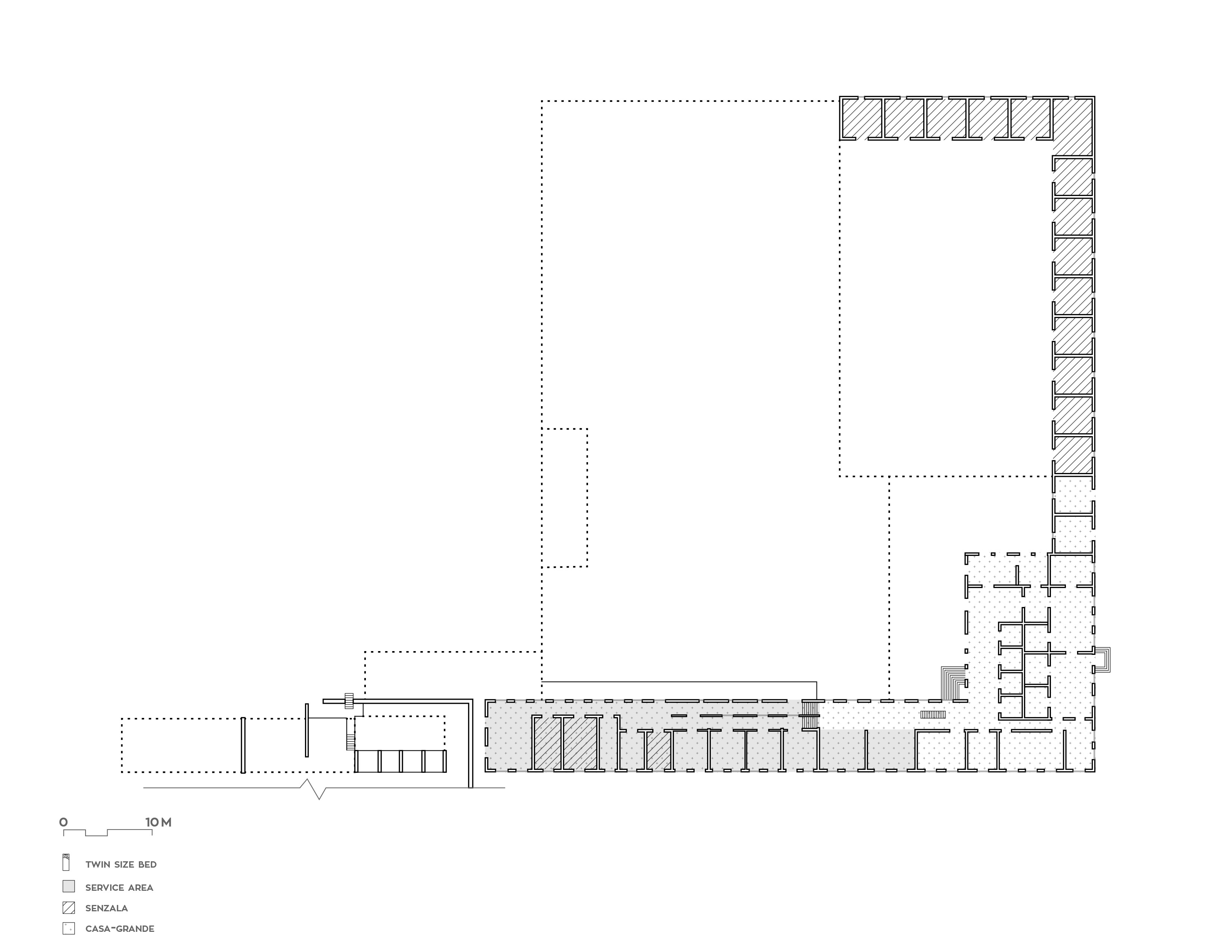

The spatial genealogy of the quartinho de empregada has historically evolved in the Brazilian household. During the Colonial Period (1530–1822), the domestic service landscape was materialized as senzalas — housing used as accommodation in the plantations for black slaves brought to Brazil between the 16th and 19th century. These plantations constituted a largely self-contained economic, social, political, and cultural system. The monoculture mills and farms managed social relations that translated into spatial delineations: Casa-grande (“Big House”) and senzalas (Fig 2). In the Casa-grande, the enslaved labor maintained the highly busy, demanding, and crowded space where the landowner’s nuclear patriarchal family performed its domestic life.17 With the rise of migration from rural to urban areas during the mid-19th century, the edícula (“outbuilding”) emerged in the urban property’s backyard.18 The pressures of urbanization in the late nineteenth century compromised the service annex’s viability, attaching it instead to the kitchen or service areas as an isolated room. Meanwhile, the building typology introduces designated service access and circulation due to the verticalization of Brazilian homes. The outcome of this evolution resulted in the quartinho de empregada.

Fig 2. Plan of Fazenda Invernada Morro Agudo

Domestic life is an accurate depiction of the broader divisions in society. The archetype of the home is a social space that creates and manipulates class, gender, and race relations. When we map the Brazilian domestic space landscape, it reveals the concerns, priorities, and values of the national social context. A range of emblematic residences in São Paulo’s region was selected to bring forward the maid’s room’s anatomy, and therefore its implications

(Fig 3)

. This exercise allows us to isolate the stage where power performance takes place.

Fig 3. Comparative table of selected residential plans