third landscape

by Anna Dietzsch

![]()

Eliane Brum, in “The dictatorship that won’t say its name” (“A ditadura que não diz seu nome”), in El Pais, Feb. 8, 2015

Or it is perhaps worse to tell someone what they are, or what they ought to be. In his article “The Origin of the Baré People,”

1

Braz França, an elder from the Baré people of the Black River Basin in northern Brazil,

asks himself what his great grandfathers would say if they could compare their good lives with his destroyed one.2 They would, he suggests, say they were not Indians. They were the Baré, the Dessana, Baniwa, Hopi, Tukano, Araweté, Guarani, Kayowá, Kamayurá, Xavante, Ashaninka,

Asurini, Yanomami, Tembé, Surui, Guajajara and so many others with their own identity, language, with their own name.

The traditional agro-forestation system in the Black River Basin, Brazil, was considered a national cultural landmark by UNESCO

Today in Latin America, we are still trying to conform a population that is highly diverse to labels of our own invention. We have created an illusion of a “minority Other” that, in reality, is greater in number and fictional in color. Sixty percent of the population in Latin America is considered non-white

and people come in many different colors. This idea of an opposite Other is nothing more than the fabrication of a dominant voice, the voice of industrial capitalism with its dependence on endless cycles of production and consumption – and a white European face.

This is a story that started in Europe in the 14th Century with the detachment of the power that emanated from the land. It is the story of the transition from a rural world and an agrarian economy to the world of the city and then to that of industry. In this modern world, the old embedded imaginary3 gave way to one centered around notions of natural individual rights; those of life, liberty and property. The old paradigm, where people felt rooted in a cohesive social group and connected to the cosmos (or some natural order) in their ontological understanding, was substituted by the exaggerated importance of the individual and by an unattainable God.

![]()

Everything is Interchangeable

In this new reality, civility became the token for citizenship and educated politeness the opposite of the savage, or the uncivilized. As we can see from these terms, the underlying contrast was really between life in the forest and life in the city. In looking for their meanings, we will see that savage comes from the French sauvage (wild), and from the Latin silvaticus (of the woods), whereas civility originally comes from the Latin civilitas, relating to citizens (or the city).4 Only in the 16th Century would the term acquire its meaning related to politeness.

Fast forward six centuries to the present where we have climate, economic, health and social justice crises. Many of us have begun to be skeptical about how our social and economic values are leading to a climate cataclysm. As an example, Teen Vogue, Salon and Money Watch reported in 2018 on the reaction of Millennials to a CNN article: 66% of them said they did not save for retirement because they believed capitalism as we know today would not exist by the time they were sixty-five.5

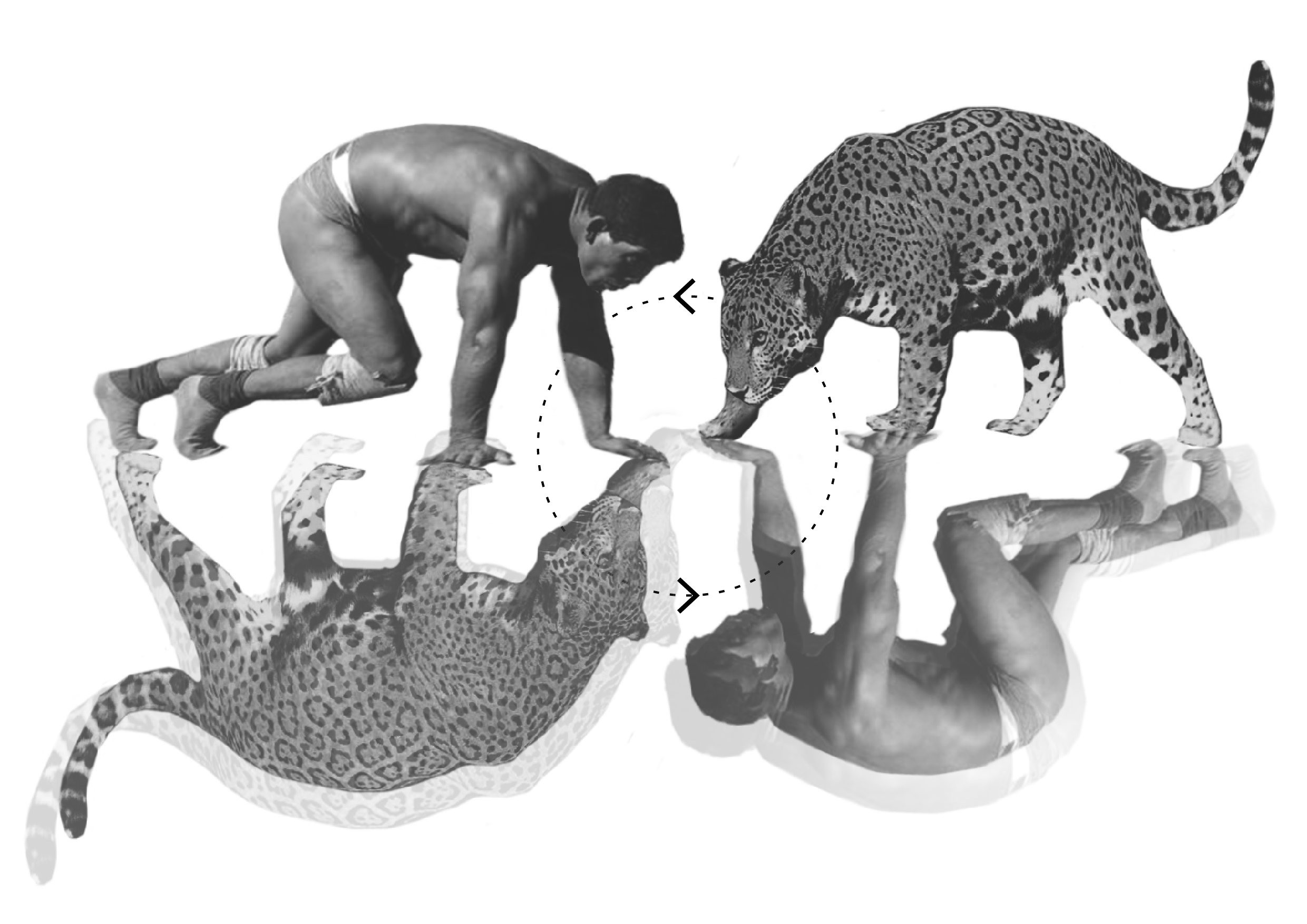

As we pivot our perspective and rebalance concepts about what is rural and urban and what it means to be savage (from the wild) and what it means to be civilized (from the city), our attention focuses again on nature and on the forest. Focusing on those who belong to the forest – those who Ailton Krenak, in his book “Ideas to Postpone the End of the World,”6 has ironically called the sub-civilized – the Indians, the Blacks, traditional riverine communities and the aborigines. All of those who, at the margins, have an organic, uncivilized layer that has kept them attached to the earth, to a circular culture7 that has quite a different sense of hierarchy between what is human, natural or divine and subjective.

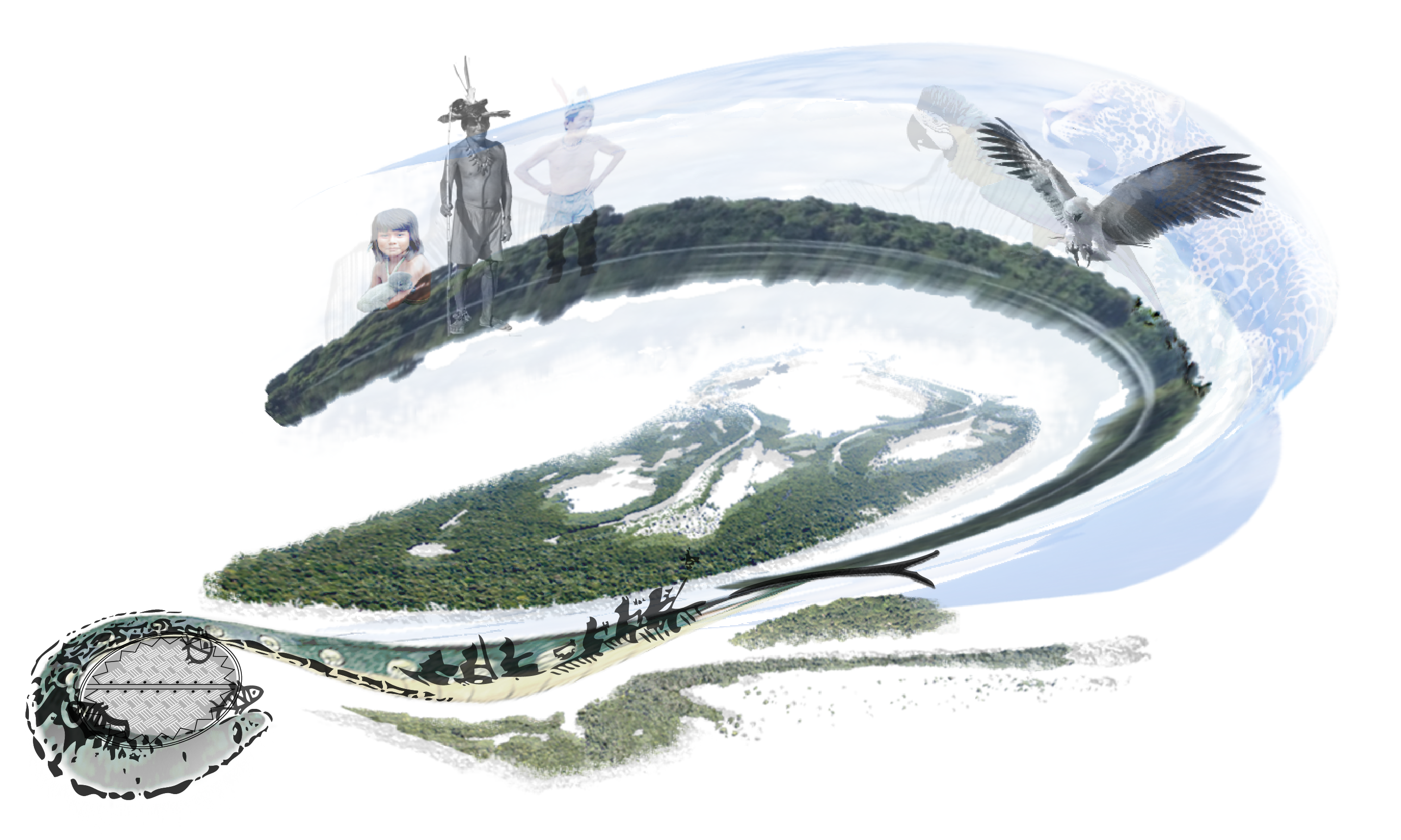

![]()

In a circular culture, man, nature and divine have a non-axial hierarchy

For them, routine elements in life are still embedded with a sense of divine importance that correlates and connects people, nature, things; what David Kopenawa and the Yanomami call the xapiri, the spirit of things.8 In this imaginary, objects are transformed into subjects. Everything

“is person” and interchangeable, as the Brazilian anthropologist Eduardo Viveiros de Castro has illustrated with his “Amerindian Perspectivism.”9 The cosmological calendar is correlated with natural, social and productive renewable cycles that defy our anxious fragmentation of time to, instead, establish modes of production that leverage nature without destroying it. Borders are fluid and territories are demarcated by their inherent natural “maps,” as well as their historic, cultural use, rather than superimposed arbitrary property lines. The mark of a collective individual also adds a different meaning to the communal use of these spaces.

However, what all of these communities, stories, traditions, songs and resistance show us, is an expanded gamete of possibilities, of different narratives that could help us, the civilized, expand our own subjectiveness to create a new landscape, a Third Landscape which is global because it is securely anchored in what is local, and is universal because it is multiple.10

![]()

In a world where nature and humans are integrated, time is fluid, space is fluid and rivers are the elements of continuity

In this new construct, two different systems of thought and practices, that of the natural and indigenous, and that of technology and capital production, could be brought together to guarantee the continued economic and environmental resilience of important “natural” regions and pave the way to interesting hybrid solutions. “Foreign” and “local” technologies could be employed within the relevance of local context in a productive encounter between natural and urban environments.

As we see the world immersed in an environmental crisis with no precedent, the idea of a Third Landscape evolves around the creation of new spatial forms. In regions like the Amazon, they could reframe the process of extended urbanization into one of extended naturalization, in order to imagine spaces that are socio-bio-diverse, and that will enable us to sustainably inhabit our forests in the long term. 11

1. Marina Herrero and Ulysses Fernandes (orgs.), Baré, Povo do Rio (Sao Paulo: Edições SESC, 2015).

2. Historically, the Baré people have inhabited the Black River Basin. They were affected by the incursions led by Portuguese colonizers in the XVIII century. Nearly decimated by epidemies, wars and enslavement, the Baré lost their native language and until today speak “Nheengatu”, an artificial language created by the Portuguese to “unify the indigenous people” in Brazil.

3. Charles Taylor, Modern Social Imaginaries (Durham: Duke University Press, 2004).

4. See Lexico.com, by Oxford Dictionary (accessed on Dec. 28, 2020).

5. Keith Spencer, “Some millennials aren’t saving for retirement because they don’t think capitalism will exist by then,” Salon, March 18, 2018.

6. Ailton Krenak, Ideas to Postpone the End of the World (Toronto: House of Anansi, 2020).

7. Anna Dietzsch, “Third Landscape, Part I: for the design of an Amazon Forest City,” The Nature of Cities, June 2, 2020.

8. Davi Kopenawa and Bruce Albert, The Falling Sky (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2013).

9. Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, The Relative Native, (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2015).

10. Anna Dietzsch, “A Visit to the Guarani-Mbya in Sao Paulo,” in The Nature of Cities, June 4, 2017.

11. Roberto Monte-Mór, “Extended Urbanization and Settlement Patterns: An Environmental Approach,” in Implosions/Explosions: Towards a Study of Planetary Urbanization, ed. Neil Brenner (Berlin: Jovis, 2914), 109-120.

Images by Anna Dietzsch and Mariana Gortan